Dear Unknown Friend,

before I talk about visions, my local bookshop and how the rhythm of our existence is bigger than the machinemen with machinehearts, let me point you towards four things.

I have re-glamoured my poetry website. Special thank you to everyone who has ever responded to my writing, your continued kind words have been put to good use, as you’ll see.

I have re-glamoured my commercial commissions website. Should you ever wonder where I get the money that I then lose giving away books and putting on esoteric events … it’s from the organisations that commission me for language. If you run a company then hey, be the patron you want to see in the world.

A reminder that I’m doing a FREE online reading of work on Wednesday June 25th, 7pm UK time. I’ll talk about writing and I’ll perform some poetry. It’ll be relaxed apart from the bits which will be intense. Get your free ticket here.

On July 19th, I and some amazing friends will be staging the first Our Longland Is Dreaming medieval poetry eco-happening in fields in Devon. (This date has been moved a couple of times because of fieldy things but the 19th is set now.) It’s inspired by the 14th century poem Piers Plowman and revolution. It’ll be like nothing else. We’ll meet in Totnes and have a bus take you to the secret location. Get your free tickets here.

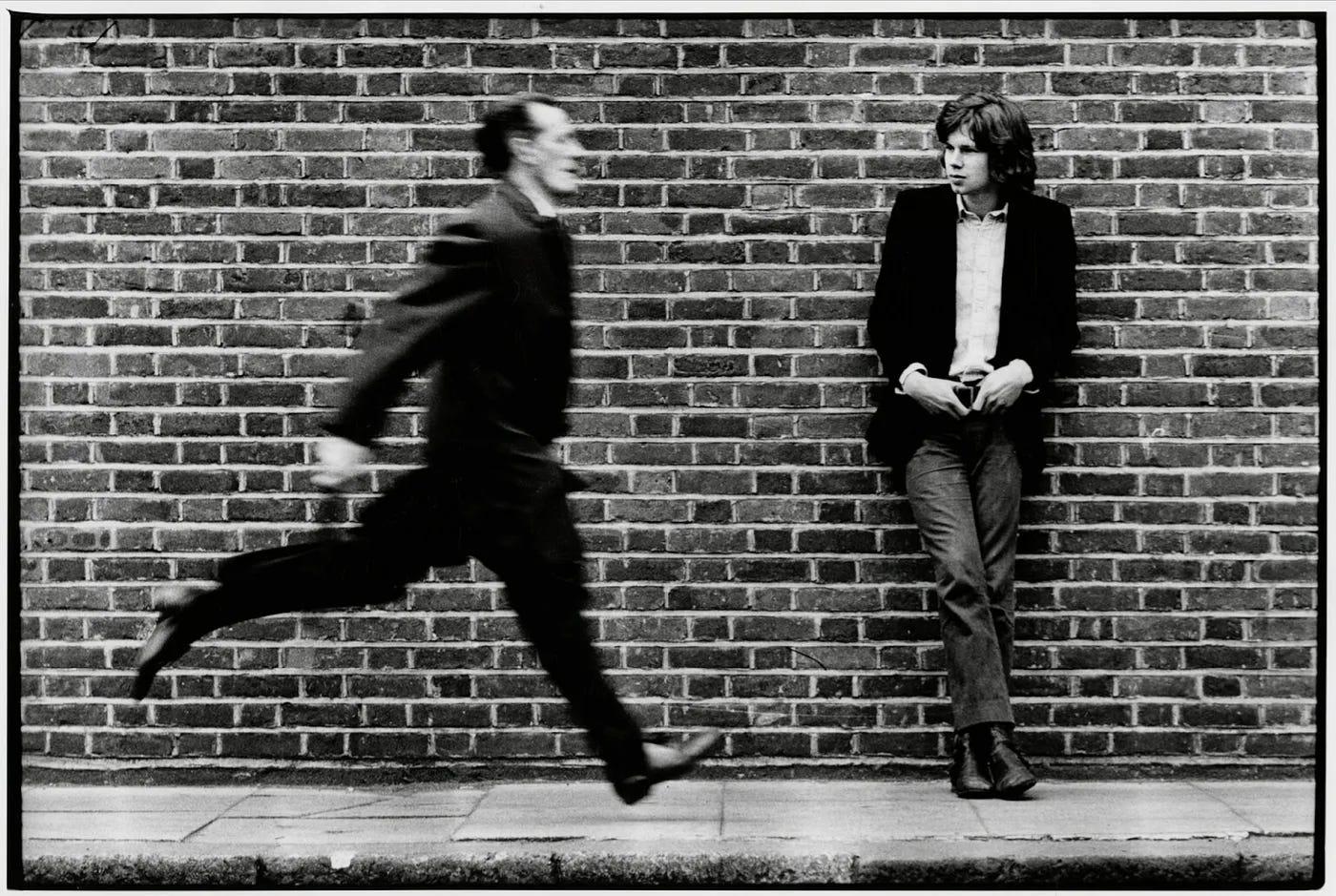

Here’s a monk dreaming in a field, like life was a memory that happened long ago.

A few Substack letters back – doesn’t time float off? – I mentioned that I recently did a solo retreat in the Malvern Hills. I wanted to draw down some new material. I meditated and entered hypnagogic states. I noted the images that came to me.

I was in the Malvern Hills because that’s where William Langland the author of Piers Plowman is believed to have lived. Well, actually, we don’t know this for certain, because we know very little about William Langland.

‘I have lived in londe quod I my name is Longe Wille’

Academics have dedicated whole lives to debating nuances of text and slight historical traces – like the above hinting at him living in London at some point, alongside a form of his name – in order to prove this or that about Langland.

Ultimately though, he’s a living mystery, a person whose life has rippled far beyond the thirteen hundreds.

In the Malvern Hills, alongside the Gnostic Noir Alien Femme Fatale vision that came to me (see this letter), I had an image of The Plowman – the main revolutionary character in Our Longland Is Dreaming. Or rather I had an image from The Plowman’s perspective.

That is I had a vision of being him lying in a meadow. The grass around him is very long. It forms a sort of oval shape, through which he can see the sky. Next to him is his lover. They are holding hands and looking at the heavens. The Plowman is melancholic, though maybe he doesn’t realise why.

The why is because soon he must die and leave his lover so that he can become a mythical figure and appear in Piers Plowman and, 800 years later, my poem.

Of the four medieval humours (sanguine, choleric, melancholic and phlegmatic) I’ve definitely always had an imbalance of the melancholic. We cannot choose the planets we are born beneath, only what we do about them. Creative activity for me is a way of keeping the black eyed dog at bay.

Hold the thought of The Plowman lying in the meadow with his lover and looking straight up.

My local bookshop, Minster Gates, is one of those bookshops that’s so Diagon Alley, cramped book-lined staircase, dark academia-ish that it’s Instagram famous.

It was a couple of years ago when I began thinking a lot about Piers Plowman as a possible project.

Amazingly and almost immediately, a huge stock of related books – studies of Piers Plowman in its many manuscript forms, as well as broader discussions of contemporaneous medieval writing – arrived on two shelves in the medieval literature section of Minster Gates.

Month by month, I began to buy them up.

One of the things I love most about good secondhand bookshops is that they have a tradition of leaving ephemera – bookmarks, letters, newspaper cuttings – in the books they sell.

Ephemera.

What a word ephemera is. I wonder if our physical forms are mere ephemera to the vast, storied reverberations of our lives.

I began finding ephemera in the Piers Plowman books I was slowly purchasing. And I gradually realised that all the books came from the library of one man.

This is the man, Derek Pearsall.

Remarkably, one of the world’s leading scholars of Piers Plowman had lived near me and his library had found its way to Minster Gates.

Ephemera.

The wonder at finding a letter from 1994 between two academics discussing arcane (and seemingly contentious) points of literature.

The intrigue of a 2000 letter from a Canadian widow gifting her husband’s posthumously-published book to the man who inspired it who, now, twenty-five years later, is also dead.

In my last letter I offered to mentor anybody that felt they needed it. As a result I’m chatting to seven or eight people. All in possession of wildly different humours.

From similar one-on-one conversations I’ve had in the past, I can say that the most common question we ALL have is the same common question all the brands I’ve ever worked with have … and that question is ‘I contain multitudes, I am formed from infinite rhymes, how can I present myself in a way that wins the game of capitalism.’

If you were interested enough to visit my re-glamoured websites, you’ll see how I play that game. We collectively understand that the machinemen with their machinehearts have designed a system that demands we package ourselves neatly for their consumption.

Our desire for encapsulation is *only* a thing because we must market ourselves.

Yet, and yet, it’s ok, because we’re going to die.

(I told you I was a melancholic.)

It’s not really melancholy. I’m with the Gnostics and the understanders of maya and the Idealists – much of what we think we know is an illusion.

And what that means is that our true story is so much bigger than the short bit when our heart beats.

This is such a weird way to promote my new websites.

A man lives on in his books. In the way the library he built up has an effect on others. In ideas contained in the letters he sent. In the people who loved him and think about him. In the strangers who discover him through the medieval literature shelves.

In the collective consciousness in other words.

One of my favourite lyrics is from Nick Drake’s Fruit Tree,

‘life is but a memory, happened long ago’

he sings, in a haunting song about being remembered after your death. Doubly haunting because he died at 26, relatively unknown, only to achieve a fame he could never have envisaged. Or, seeing as he wrote Fruit Tree, a fame he maybe did envisage.

The writing below is from the first passus of Our Longland Is Dreaming. It comes from the vision I had. The Plowman lying with his girl and looking at the sky, whilst the melancholy of his slipping into myth hangs over them.

It’s in three sets of three verses. Each set of three verses follows a similar metrical pattern and form, whilst the imagery and language becomes more intoxicated. I wanted to hint at the rising mad tension in The Plowman as he approaches his end.

But it isn’t really an end. Just another column in a cathedral of time. Like all of us, he’ll live on.

The Plowman’s Sacrifice Many sown summers ago, when the Plowman was bright flesh, when he could pick motes of dirt from his hob boots and his nails after tendering the day in the fields of his life, he would lie the banqueted, bosomy meadow with his longgrass girl, living deep in evening dew. ‘We’re reclining in a crown’ she’d say and they’d hold the oval of sky in their twinned, unfurling eyes, watch it polished by clouds, honeysweet blue to old-chestnut black. They’d lie sunk below godsmith-worked stalks, high-jewelling insects, the regal shimmer of leaving heat. Stretched in their cold cocoon, hands held like a tomb. All those danced harvests ago, when the Plowman was ox brown, when he could leap country stiles country ringing like a bell after working the hours in the furrows of his maybe, he would lie the balming, buttered meadow with his falldown girl, kissing slow in sun’s disappear. ‘We float in a chalice’ she’d say and they’d hold the eye of heaven in their shared vesper regard, watch it speckled by rooks tearing their dark way home. They’d drift on the wine of the ground, beneath waving green lips and the priests of the hills. They'd curl aside in their daisy’d cave, pressed together like the grave. Circled seasons ago, when the Plowman was heart full, when he could laugh like the hedge, vast and green green shouldered roar, after swathing the gleam from the crops of his given, he would lie the primrose bellowing meadow with his song of songs girl, psalming secret in her. ‘We’re mouthed in a beast’ she’d say and they’d hold the last of the light in their wild-married look, watch it theatre the gnats who build cathedrals of time. They’d be howled by their hollow, rough canticles of stem to cower the night. And they’d float on that acre’s breath. And they’d float in their aching death.

I love this. A long time ago I knew Robert Kirby who arranged some of the five leaves tracks on Nick Drake's album. He worked in the telephone unit of a market research company and used to stand in the carpark with me smoking cigarettes. Since then I've met two of the kindest people I know who worked in the telephone unit of that company. So did my cousin after he was recovering from TB. There is connect and magic and music everywhere.

A beautiful, peaceful and deeply fulfilling poem. Thank you