'Language is a virus from outer space'

Suns. Williams. Poetry IP. Ancient stillness. Searching for stylometry software.

I’m a Creative Director and poet. I’ve spent my life thinking about what writing can do. I work with exciting organisations to invent worlds, campaigns and artistic moments with language at their heart. I release new poetic objects every four months. I was the world’s second most awarded studio in the 2020 D&AD awards. This is a regular letter about my thinking and my work in progress.

Hi. I’m going to share now, tell me if you can see it.

I’ve been doing talks to universities recently. Over Zoom of course. I get invited to do these by design course tutors and they nearly always say the same thing.

‘It would be good for our design students to hear about the importance of words in design.’

‘Words’, not writing. Somewhere, in one of Hugh Everett’s branched-off many worlds, there is a designer Tom Sharp being asked to give talks to groups of student writers as ‘it would be good for them to hear about the importance of shapes in writing.’

Maybe that sounds snooty. I don’t mean it to be so. The tutors are lovely and are not to know my personal bugbears about the phrases ‘copywriting’ and ‘the importance of words’.

But I am always amazed at the idea that whole courses of intelligent, creative young people need me to tell them what writing can do.

For last week’s talks I invented a demonstration of why writing is powermagic. Here it is.

I begin by saying that simple images are much more useful than simple writing in conveying basic information.

So a simple picture of a sun …

… offers us ideas of ‘sun’, ‘health’, ‘fun’, ‘children’, ‘light’, ‘happiness’. Simple, immediate notions. That’s why this kind of iconography appears in packaging and other places when there is little time to get attention. Whilst the word …

SUN

… only really describes the sun. Actually, it doesn’t even describe it. It just reminds us of the object. The simplest writing does far less than the simplest image.

But things get interesting when you increase complexity. A slightly more complex picture of a sun …

… doesn’t really offer much more than the ideas that came from our crude illustration. Sure the execution is more sophisticated, but the *information* is the same. You’d need more context, maybe even Van Gogh’s tragic backstory, to make the viewer experience an increase in qualia.

But a slightly more complex piece of writing using the word sun …

A sunmess of daisies.

We choose to go to the sun.

Your childhood suns miss you.

… can offer almost complete worlds and sudden, blazing emotion. An echo of JFK in choosing to go to the sun. The strangeness of pairing ‘sun’ and ‘mess’ together and the romance of daisies being described in such a way. Your own memory as it reaches back to the long-gone suns you once knew. Remember that holiday? That one where you discovered …?

There is a disproportionate deepening of story and feeling through a small increase of complexity from ‘sun’ to a crafted sentence. Quicker than painting too.

And that’s what writing can do. No idea what the students thought of my thought, Zoom is not designed for real feedback. Substack is though, so tell me what YOU think.

In this letter I’m going to be sunny about William Burroughs, William Morris, IP and an advert I’ve written, plus an update on my attempts at textual analysis.

I studied the Beat Poets with Dr Oliver Harris, the editor of William Burroughs’ letters. He had some good and sleazy stories of hanging with El Hombre Invisible, and I first heard the news that Allen Ginsberg had died from him. I’ve always loved the hypnotic, intoxicating quality that Burroughs’ experimental cut-up novels such as The Soft Machine and The Ticket That Exploded have. Created with Brion Gysin, Burroughs’ technique involved chopping up his own typewritten text and then randomly rearranging it, sometimes with text from other sources. Introducing chaos into the writing process. As we all should.

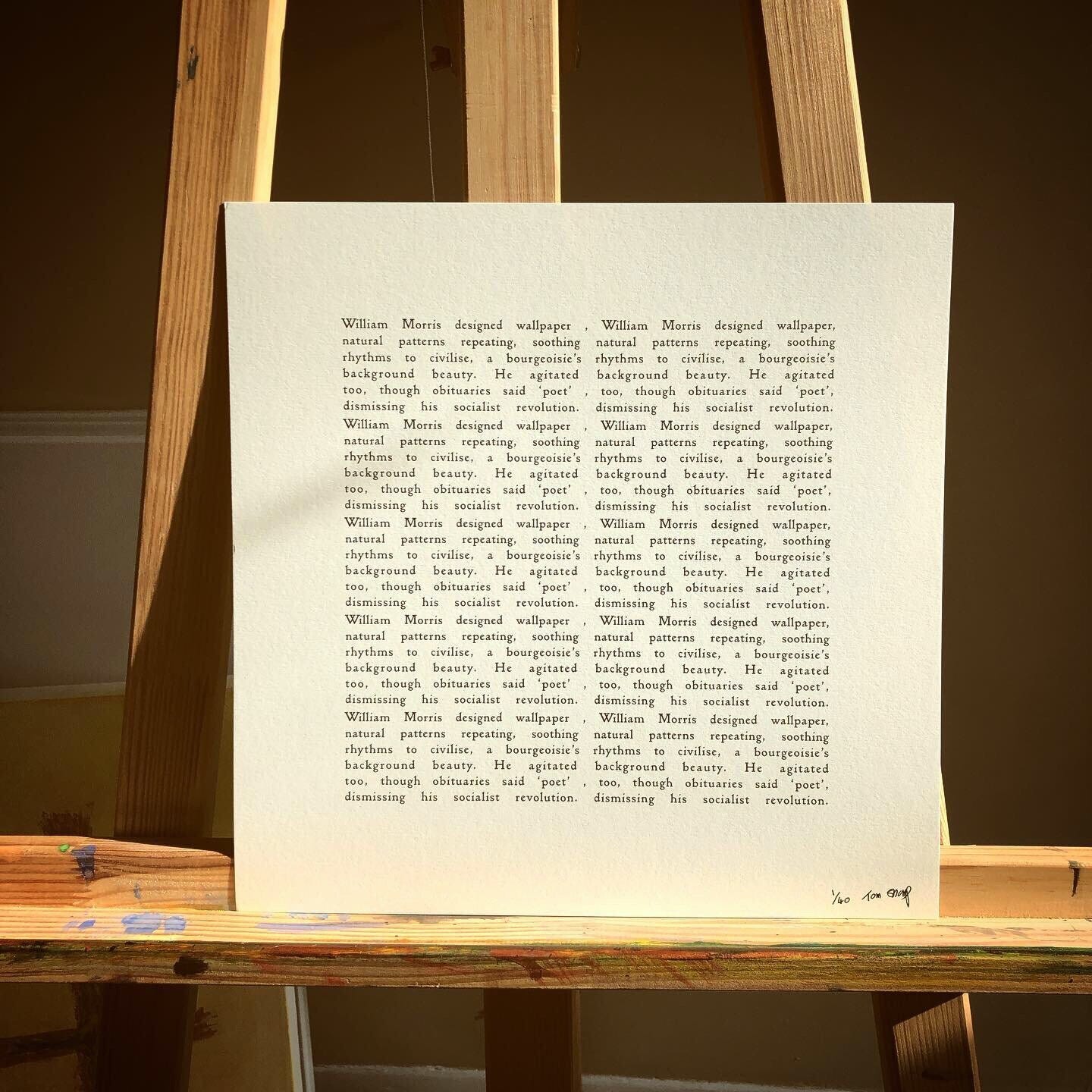

The above piece is something I wrote and designed for the Bloomsbury Festival. I won a D&AD Wood pencil for it. It’s about William Morris but it’s influenced by William Burroughs and cut-up. The piece is 260 words, made up of a single 26 word block repeated 10 times in two columns and five rows, in the manner of wallpaper printing. (William Morris designed and printed wallpaper.)

I arranged the rivers between the text (the spaces that aren’t letterforms) to resemble the tendrils you find in Morris’s patterns. And whilst not a cut-up, I was trying to replicate that odd effect that cut-up can have. You can read the 26 words in a block but also in lines running fully from left to right. It *nearly* makes sense. It feels like it *should* make sense. Some bits *do* make sense. Recreating that point where your mind just gives up and goes with it. All the best trips happen like that, right? That’s what cut-up can do. I’ve been trying for ages to find a client interesting enough to embrace cut-up in their brand.

Since January and throughout the first UK lockdown I’ve been working on a long poem called myu. It’s about the thoughts of the universe over the course of one second in 1913. I was sent Active Imagination journeys from my Instagram followers to include in one section – I like the idea of crowd sourcing images from the collective unconscious – and the work is about prophesy and shamans and panpsychism. My work is hardly blockbuster material anyway but this is really pushing it.

(That’s a mandala I painted which appears in the front of the book.) Part of the focus in this series of email letters is the business business of writing. Not just the craft business. I’m an independent poet, what the gatekeepers would sniffily call ‘self-published’, so every time I have new work to publish I have to figure out how to fund it. I think of myself as my own patron, people pay me money to make brands and do advertising which I plough into expensive print techniques and complicated bindings.

I’d been hoping to release muy on December 6th as that’s the date Thomas Aquinas had one of his ecstasies and he pops up in the poem a lot. But I’ve earned nowhere near enough to fund the print run yet, thanks Covid, so it won’t happen. There’s a peculiar kind of unsharable frustration when a self-imposed, arbitrary and entirely unknown-to-anyone-but-you deadline passes by.

Anyway, I tell you this because I did have what I think is a novel idea about how writers could fund publications. I’m considering offering a portion of the IP of myu for sale, alongside the book. So for £15 you can buy the release, but for £250 you can get 10% or something of IP rights in perpetuity. It’s basically a gamble on my future success. I’m going to think about this some more, but I really like it. I think as writers we should own our means of production and must continually seek out new models. And I always loved Bowie Bonds.

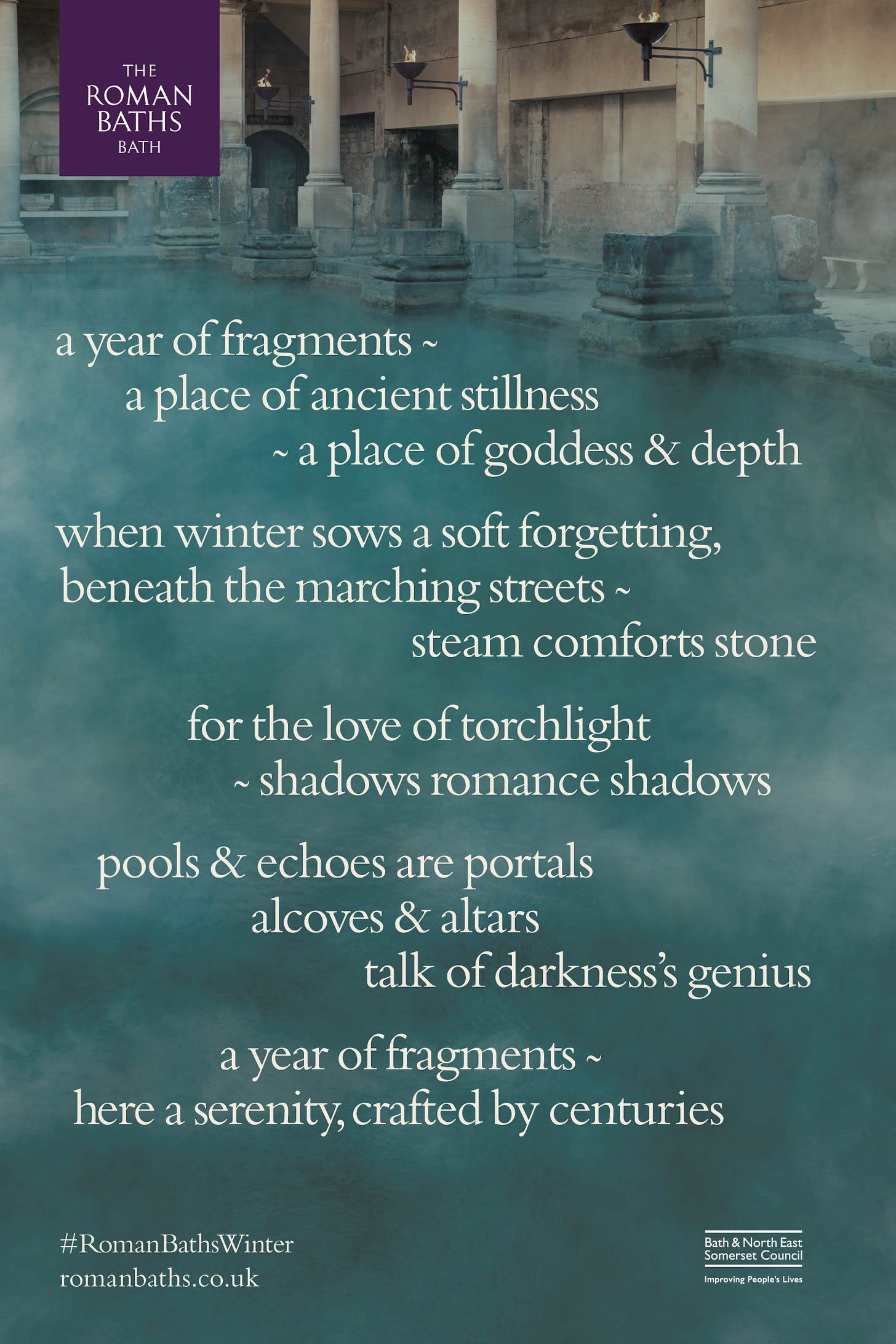

Here’s an ad I’ve written for The Roman Baths in Bath. It’s on the London tube as well as the radio. I wanted to write something that felt ambient and appeared to be in fragments. Partly to reflect the strange drifting, fragmentary year 2020 has been, but also to reference an 8th century Old English elegy called 'The Ruin', which appears in the fire-damaged 'Exeter Book'. The burnt pages have gaps but seem to mention the Roman Baths in partial glimpses. The scattered lines and images mirror this.

The client wanted me to do what I do and the finished piece is the first draft, they didn’t change a thing. When writing a commercial piece like this, in which my particular music is what a client is asking for, I think it must be like being a composer of film soundtracks. You’re bought for your style and all you have to do is fit it around the plot points. The ads are elegantly designed by Steers McGillan Eves.

In my last letter I mentioned that I was trying to figure out how to do a textual analysis of my writing so I could try and not write like me. Well, I’ve learnt what the textual analysis process is called – Stylometry. And I’ve learnt that the basics were invented in 1890. And that in the 1960s the Rev. A. Q. Morton did a computer analysis of St Paul’s Epistles, which indicated that six different authors had written them. Then someone applied his method to James Joyce’s Ulysses and found that that was composed by five different people. (It wasn’t.) The whole field is still relatively experimental.

I’ve spent a lot of time trying to download amateur stylometry software from obscure academic corners of the internet and although, amazingly, I have no malware to show for it … I also don’t have any working stylometry software. The hunt continues.

Thanks for listening. You truly are suns.

Tom