Language, consciousness, magick and romance is the golden thread of ideas I’ve promised myself I will play with forever.

As you’ll know if you came to my TypoCircle talk at the close of last year, the formula goes like this – mastery of language enables one to influence the sea of consciousness (starting with your own) and consciousness is the base layer of reality, which means the more you can shape it, the more you can enact magick (which is simply sculpting reality to your will) and the only reality-sculpting worthy of a human life is an egoless pursuit of the ultimate romance – that of tickling the divine.

I also write ads for money.

Carved in stone on the original HQ of the CIA is the verse ‘And ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free’ found in John in the King James Bible.

Which is a jaunty bit of language (anapaest / anapaest / anapaest / iamb / iamb) about getting to the base layer of reality and using that to transcend.

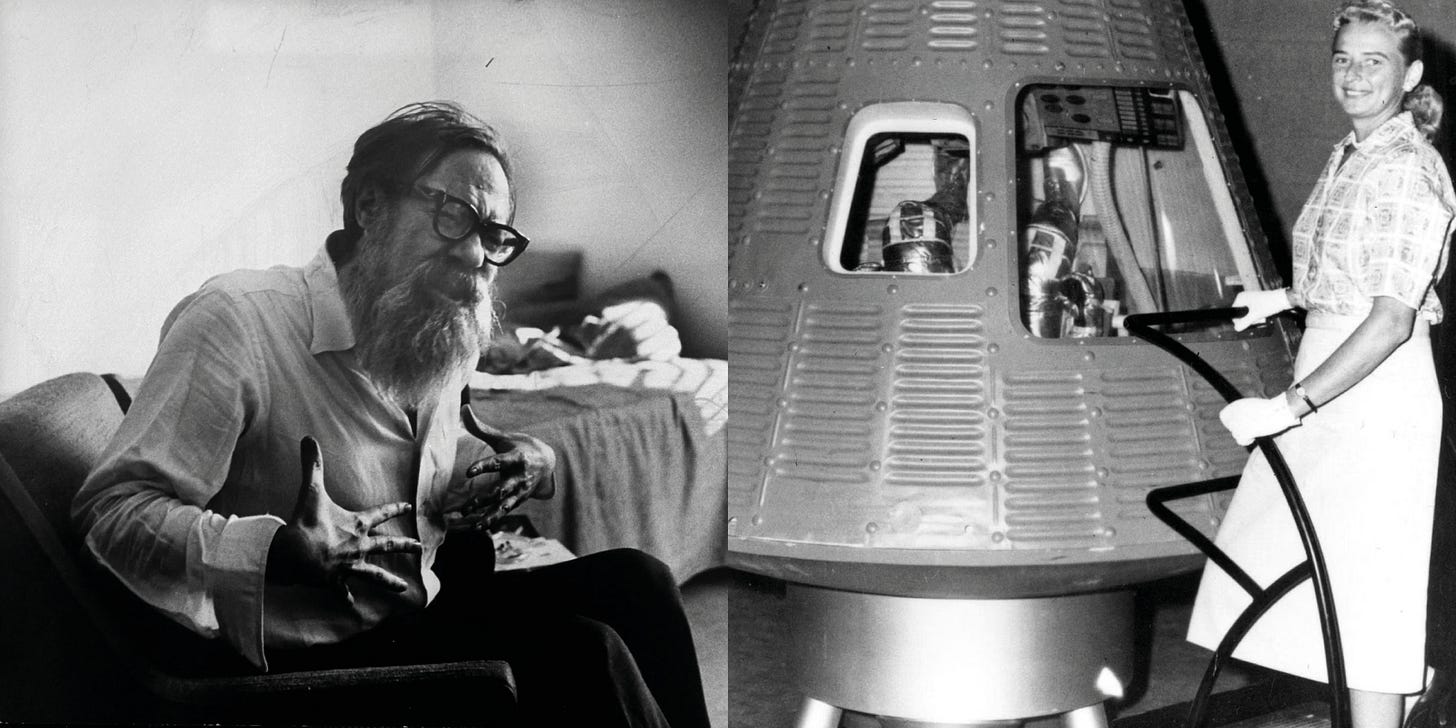

That’s open-mouthed, transcending Carl Pfeiffer, CIA researcher and chairman of Emory University's Pharmacological Department, being given LSD 25 in 1955. The experiment was documented using the microphone. As part of the notorious MKULTRA programme Pfeiffer gave LSD in turn to prison inmates and studied the results.

The truth shall make you free.

As I assume is clear from my previous Substacks, I spend a lot of time sifting through the wastebaskets of various fields of study in the hope of discovering nuggets of thought to inform the whole language, consciousness, magick, romance thing.

I’m interested in the technical language / consciousness end – how writing can influence mental experience – and the philosophical magick / romance end – what’s it all about etc.

I think this specific Substack letter is about both. It’s a half-formed spooky thesis. Perhaps the beginning of a realisation, perhaps the beginning of a rabbit hole tumble. It’s all very obscure and absolutely no help to your career aspirations, time-management toolbox or tangled love life. It does have some moments of high strangeness though and it says here on your file that your 2024 midnight wish was for more high strangeness.

What if poets and spies are engaged in the very same activity? What if the world began to realise it was just the same game? Two sides of the same coin. What then? What would it mean for all our divisions between art and international artifice? Our separation of statecraft and, well, just craft?

We are taught from such an early age that some ways of spending a life have consequence and gravitas and import … and other ways are – as clients who rarely remain clients for very long occasionally say to me – ‘arty-farty’ or ‘airy-fairy’.

(Memo: af, af. Must be something about that procession of letters which encodes a frippery. Will keep under surveillance.)

You’re doubtful. You’re thinking yes, but when the CIA moves pieces around the devil’s chessboard and a bomb explodes in a way which destabilises a government, that’s incomparable to a writer moving language around a page to destabilise a reader’s heart.

Maybe.

‘Politics is downstream of culture’ said right-wing writer and publisher Andrew Breitbart, whose premature death at 43 raised KGB assassination rumours.

It’s a saying I’ve always liked. The idea that we change the world by creating its egregores, rather than trusting an elected official to do the right thing.

And contrast that with the devastating street-side explosion some far-off agents secretly funded four paragraphs back. Sure, those scheming skulkers in shadows *hope* for regime change … but the outcome of their machinations is rarely predictable.

In fact I think poetry is *more* influential than the dark whispers against it make out … and spycraft is *less* directing than its budget-hungry bugs claim in long squeaky corridors.

The following document contains some recent observations. For focus sake I’m going to limit my discussion of spycraft to the CIA in the mid-part of the 20th century. A time when the American empire was at its manipulative, confident height and a time which is now relatively well documented.

Field report 1

Let’s begin by comparing John Berryman’s Pulitzer Prize winning 77 Dream Songs with a bizarre case of doubling buried on the outskirts of JFK lore.

Berryman’s 77 Dream Songs was published in 1964, he had been writing them for a decade or so. Each dream song is made of three six-line stanzas. Each concerns a man called Henry who is remarkably like Berryman himself. They are wild and obscure and baffling and delightful and surreal and brilliant. Because each dream song follows an experience of the same character, the collection could be viewed as a single, long poem. But any kind of chronology or development or structure is almost impossible to discern. The creeping confusion you feel is undoubtedly key to the book’s powers.

But that’s ok, right? A poet crafts 77 individual poems which all mention Henry, who *seems* to have a relatively consistent character, and there’s no need for a grand narrative arc at all? But it’s interesting then to understand that for years Berryman wrestled with the writing to try and determine its shape.

In an unpublished note in 1961 he wrote ‘the manuscript – of this pseudo-poem epic – was found in an abandoned keyhole and transmitted to me by enemies, anxious to thwart my lawful work. It is doubtful whether its author – of whom nothing is known, expect that he claims to be a human being, and male – gave it a final form.’

Note the use of the classical form ‘epic’. In fact Berryman applied a number of potential structures to his ordering of the 77 pieces – including a mirror of Dante’s Divine Comedy, the categories set out by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, a specific liturgical grouping of the Bible, and something that resembled The Iliad. Eventually he divided them into seven books of unequal length.

The problem really bothered him. Quoting from John Haffenden in his 1980 book John Berryman, A Critical Commentary …

‘His lack of prevenient purpose gave him hundreds of hours of unrest – indeed distress – for what seemed to be in question was the notion less of ‘preconceived theme’ than of ‘preconceived plot’ … the relationship between all units grew ineluctable even to Berryman himself.’

A new book by Mary Haverstick about Jerrie Cobb has just been released. Strap in because the story I’m about to tell you is *exactly* how reality would work if we lived inside a very big, unstructured poem.

Haverstick, an independent filmmaker, wanted to make a film about Jerrie Cobb who was the leader of a group of women pilots pushing to qualify as astronauts in the early 1960s.

In the 1950s Cobb was a famous aviatrix. She initiated the Mercury 13 program – thirteen American women who took part in a privately funded scheme aiming to test and screen women for spaceflight. She later appeared before Congress to promote the concept of women astronauts. Even later she was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. She was impressive.

Haverstick meets Cobb and in 2009 begins two years of research, interviews and preparation. Then, whilst Haverstick is on a camping holiday, a woman sets up a tent next to hers and introduces herself. She explains she works for the U.S. Defence Department and hints that she’s involved in espionage. She integrates herself into Haverstick’s life for a few months and – whenever the subject of the film about Cobb comes up – drops heavy suggestions that she should step away from the subject. Then she disappears.

Intrigued, Haverstick does some searches around ‘Cobb’ and ‘CIA’. (I’m indebted to the brilliant JFK Facts substack for this overview of the tale.)

What emerges is a trove of congressional investigative files on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, in which a CIA operative named ‘June Cobb’ is frequently mentioned.

June Cobb was a CIA spy during the Cold War. A secretary and translator to Fidel Castro. She was from the same town, Ponca City, Oklahoma, as Jerrie Cobb. Both were part of the civil air patrol, both learned to fly planes at an early age.

Both had lived in Norman, Oklahoma. Both were blond and of the same height and build. Both were fluent in Spanish. Both left home in their early 20s for South America and worked with indigenous Amazonian tribes in the 1950s.

June Cobb worked for an aviation company in Guayaquil, Ecuador, while Jerrie Cobb was arrested for spying in the same city. Both were interacting with the upper crust of South and Latin American societies. Both were in Mexico City six weeks before JFK’s death.

I know what you’re thinking. But you’re wrong.

Haverstick proves that June Cobb and Jerrie Cobb were two actual, separate people, with their own families and verifiable histories.

And when Haverstick brings up June with Jerrie she says …

‘Oh yes, June.’

‘Everything she says is a lie.’

Haverstick asks if June Cobb may know who killed Kennedy and Jerrie replies …

‘Yes, but no one would believe her.’

Once again, this is what reality would look like if it was being scripted by someone who did not care whether anything was logical.

There’s another woman involved too, Catherine Quinby Taaffe, an arms dealer in Central and South America during the 1950s and 60s. By matching up documented timelines, Haverstick posits that Jerrie maybe sometimes wore Taaffe’s identity as well as somehow having her life synchronistic with June Cobb’s.

And here’s some real high strangeness. The scars. Taaffe had the date ‘July 26’ (a key Cuban revolution date) carved into her arm by avenging Castro soldiers. June Cobb too had a prominent scar near her clavicle from a parasite wound incurred in South America.

Haverstick detected both scars on Jerrie.

‘His lack of prevenient purpose gave him hundreds of hours of unrest – indeed distress – for what seemed to be in question was the notion less of ‘preconceived theme’ than of ‘preconceived plot’ … the relationship between all units grew ineluctable even to Berryman himself.’

‘A wilderness of mirrors’ is an lovely line isn’t it? I’ll shortly tell you who wrote it, but it was used by spy chief James Jesus Angleton – who we’ll meet in a bit – to describe his world. A world where nothing makes sense. A world where to seek the verifiable or meaningful or John’s biblical ‘truth’ is to face hundreds of hours of unrest.

Just like poetry you can read the elements of the above in any way you want. And just like poetry the uncertainty is not an artefact of lacking information but a feature integral to the experience.

The JFK rhyme by the way is that Jerrie Cobb (the pilot not the agent) admitted to Mary Haverstick that on November 22, 1963, she was idling a plane for hours at Redbird airport a few miles away from Elm Street, where Kennedy was shot. Haverstick doesn’t believe this and thinks Cobb is actually the mysterious, never-been-tracked-down Babushka Lady seen taking a photograph at the exact moment of the head shot.

John Berryman writes in Dream Song 77 …

—Henry is tired of the winter, & haircuts, & a squeamish comfy ruin-prone proud national mind, & Spring (in the city so called). Henry likes Fall. Hé would be prepared to líve in a world of Fáll for ever, impenitent Henry. But the snows and summers grieve & dream;

Field report 2

The brilliant William Burroughs – or El Hombre Invisible as the Tangier locals would call him – choose to write his way out of the galactic control mechanism rather than HUMINT – as the CIA refer to human intelligence – his way out.

Field report 3

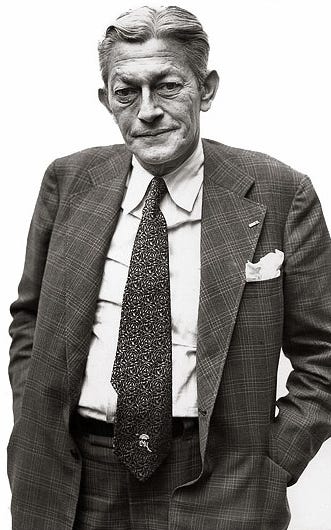

James Jesus Angleton was the strangest agent. Brilliant and charismatic (and alcoholic and eccentric), he was one of the most powerful CIA spymasters of the 20th century. He had a hand in most of the international dark politics incidents you can think of. If JFK’s murder *was* a CIA plot then Angleton would have orchestrated it.

He used the phrase ‘a wilderness of mirrors’ to portray his craft and took it from T.S. Eliot’s ‘Gerontion’ …

These with a thousand small deliberations Protract the profit of their chilled delirium, Excite the membrane, when the sense has cooled, With pungent sauces, multiply variety In a wilderness of mirrors. What will the spider do Suspend its operations, will the weevil Delay?

He knew Eliot. They were very similar. Both dressed conservatively, had hollowed faces, similar grave airs and American-cultivated-in-England affectations and backgrounds. That’s Angleton below, but it might as well be Eliot. Doubles everywhere.

‘Eliot was simply monumental’ Angleton said ‘but Eliot killed poetry.’ James Jesus Angleton loved poetry you see. As a student at Yale he inveigled a university paper interview with Ezra Pound and stayed with him for five days. As Jefferson Morely in ‘The Ghost’ explains …

‘Pound’s reckless ambition, his will to cultural power, his elitism, his conspiratorial convictions, his self-taught craftsmanship, and his omnivorous powers of observation – all these would have influence on the maturing mind of James Angleton.’

What would have even more influence on Angleton’s future in espionage though would be the New Critics of 1930s Yale and William Empson’s ‘Seven Types of Ambiguity’ – a school of thought and a key book which argue for close reading of texts, particularly of poetry, to delight in ambiguities, puzzles and an awareness of a work of literature as a self-contained, self-referential aesthetic object.

Morely again …

‘[Angleton] would come to value coded language, textual analysis, ambiguity, and close control as the means to illuminate the amoral arts of spying … literary criticism led him the profession of secret intelligence.’

What did he mean Eliot killed poetry? Angleton’s obituary in the Washington Times considered the statement …

‘Angleton believed Eliot ‘killed poetry’ by rendering it so complicated that it tied itself in incomprehensible knots. The author of ‘The Waste Land’ turned poetry into an art form that was so difficult that only he was smart enough to practice it. Angleton … had had a similar effect upon the spy business. He transformed spying into such an involuted, convoluted, labyrinthine maze that the CIA often got lost in its own intricacies.’

I illustrate my last point about Angleton with an image taken from the Principia Discordia – the incredibly influential Discordian religious text, first written in 1963 by Greg Hill and Kerry Thornley. As a high strangeness aside, in 1959 Kerry Thornley was in the same radar operator unit as Lee Harvey Oswald, the accused assassin of JFK, and wrote a book about Oswald before November 22nd 1963.

Thornley bore a distinct resemblance to Oswald and was ultimately accused by Jim Garrison – famously played by Kevin Costner in JFK – of being a ‘second Oswald’. Doubles everywhere.

The truth shall make you free.

Field report 4

Percy Bysshe Shelley once saw his doppelgänger as Saltburn fans will know. He also wrote in an 1821 essay …

‘CIA agents are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they inspire; the influence which is moved not, but moves. CIA agents are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.’

Field report 5

I leave you with a poem from my Selected Workings. I thought this was just about being comfortable with ambiguity in a frightening world, but now I’ve done the reconnaissance above, maybe it was my application letter to the CIA all along.

It doesn’t matter that you don’t know the story, no one does

Below my skylight a bowl of tea

evaporates. It meets a blue morning

falling. Ceremony of atoms. Then

that ol’ segregationist Governor Wallace

gets shot in 1972 and Nixon sends

E. Howard Hunt to softly secrete

Democratic literature about the lone nut’s flat.

Book depositories are tricks and taught

history is the torturer’s horse –

comforting distractors, evil as steaming event

rather than dark actors endlessly transmuting,

quantum slipping from snapshot background bushblur

to forum theory glimpses in frame-by-frame Zapruders

to butterfly beats of autoplaying TV loops.

It doesn’t matter that you don’t know the story,

no one does. The blue morning is falling again.

Fantastic, like the essence of parallel echoes of potential Christopher Priest (and a little pinch of Pynchon)